BENGAL HEALTH

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY (HCM)

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM - A GUIDE FOR BENGAL BREEDERS

An article written by Sue Moreland MRCVS, Bengal CC Committee member and GCCF Veterinary Officer

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM - A GUIDE FOR BENGAL BREEDERS

An article written by Sue Moreland MRCVS, Bengal CC Committee member and GCCF Veterinary Officer

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease which we should all be aware of and do our best to eliminate from our breeding lines. HCM is the most common form of heart disease in cats and affects many species of wild cat as well as all domestic cats – pedigree and non-pedigree. In fact HCM affects most mammals including humans. The incidence of HCM varies between breeds. There is very little validated data on the incidences in different breeds. The reference cited is based on data provided by motivated breeders and may not be truly representative but indicates an average susceptibility comparable to many other breeds. I am not going to cover the pathology and clinical features of HCM in great detail as there are many good recent articles and websites covering these topics. Some of these are listed at the end. I am going to talk mainly about practical things we can do to reduce the risk of HCM and put forward a few suggestions for ways GCCF can help us do this.

WHAT IS HCM?

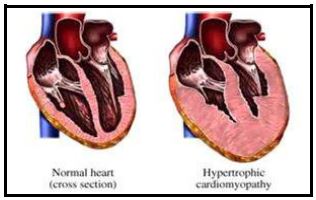

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy means enlargement or thickening of the myocardium – the muscular heart wall.

WHAT IS HCM?

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy means enlargement or thickening of the myocardium – the muscular heart wall.

It does have a number of causes, but the one we are concerned with is Hereditary HCM. This is caused by a defect in a gene coding for a particular protein ( the MYBPC3 or cardiac myosin binding protein C gene) in the cardiac muscle cells (myocytes) that make up the heart wall. When the gene is defective the cardiac muscle cells are abnormal and do not contract properly. The result of this is that the heart produces more muscle cells to compensate eventually resulting in gross thickening.

The consequences of myocardial thickening depend on the severity. They include reduced contractility of the myocardium, obliteration of the ventricular cavities, and distortion of the atrioventricular valves. The end result is that the ventricles cannot relax and fill properly, the mitral valve becomes distorted leading to regurgitation and the output of the heart is reduced. This results in progressive congestive heart failure with classic signs of lethargy, reduced exercise tolerance and increased respiratory rate even at rest.

The consequences of myocardial thickening depend on the severity. They include reduced contractility of the myocardium, obliteration of the ventricular cavities, and distortion of the atrioventricular valves. The end result is that the ventricles cannot relax and fill properly, the mitral valve becomes distorted leading to regurgitation and the output of the heart is reduced. This results in progressive congestive heart failure with classic signs of lethargy, reduced exercise tolerance and increased respiratory rate even at rest.

The other main effect is due to slowing of the blood flow through the heart which leads to sludging, which predisposes to clot formation. Detachment of a clot can occur and typically this lodges at the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta, obstructing the blood supply and causing painful paralysis of the hind limbs which is very distressing for the poor cat. Finally the gross thickening of the heart can lead to conduction disturbances and arrhythmia. This is believed to be the mechanism by which sudden death, another common consequence of HCM, can occur.

GENETICS

Early studies in a colony of Maine Coons indicated that HCM is caused by a defect in an autosomal dominant gene. However the situation is nowhere near as simple as that. In common with many other genetic diseases the defective gene shows extremely varied expression. Certainly there is incomplete dominance and in DNA tested Ragdolls and Maine Coons, cats with one copy of the gene (heterozygous) seem to be less severely affected than cats with two copies of the defective gene (homozygous).

DNA tests for the defective HCM gene are now commercially available in Maine Coons and Ragdolls. Studies in these breeds confirm this is the case. An interesting study in DNA tested Ragdolls showed very little difference in mortality to 12 years between normal and heterozygous cats. In homozygous cats there was around 50% mortality by 5 years but 20% of cats were still alive at 12 years showing that HCM is not necessarily a death sentence. It is likely that a similar situation exists in Bengals. It certainly explains why kittens who die of HCM at an early age can be born to parents (presumably heterozygous) who show no sign of HCM by echocardiography as young adults. In terms of the clinical picture the pattern can resemble a disease caused by a recessive gene. It also means that echocardiography alone does not necessarily detect affected cats – especially heterozygous ones. For this reason it is not yet possible to completely prevent HCM by echocardiography alone.

Another problem is that there are also many different mutations of this gene so it is possible that a DNA test that is developed to identify a single mutation may not detect all cases of HCM in a breed if the problem is due to several different mutations. This does seem to be the case in Maine Coons where cases of HCM have been recorded in cats which give a Normal result with the DNA test. In this situation breeders may need to continue to scan their cats annually.

PREVENTION OF HCM IN BENGALS

Sadly we have no validated DNA test for HCM in Bengals yet. Research is ongoing and recent advances have been made so hopefully a commercial test will be available but probably not for 2-3 more years. We must also remember that any mutation for which a test is developed may not be the only one.

The only way we have of detecting sub-clinical HCM in our cats is screening by echocardiography The main problem with this is that variable expression of the HCM gene means that many affected cats do not develop detectable echocardiographic changes until they are more than 1-2 years, ie the ages when most of us want to start breeding from our cats. Some cats, especially heterozygous ones, may never develop clinical signs of HCM and unless scanned well into middle age long after they have been neutered and retired we will never know they were affected. Other problems are cost as the scan needs to be repeated annually and there may be a considerable distance to travel to a qualified cardiologist.

IN THE MEANTIME, WHAT CAN WE DO TO REDUCE THE RISK?

1.Buy from echo tested lines. Now that more people scanning their cats annually under university schemes or other qualified veterinary cardiologists it is easier to buy a kitten from echo screened parents and where possible the grandparents also.

2. Do research pedigrees when buying breeding cats. Some on-line resources giving HCM test results for Bengals are available but these are incomplete and may not always be valid.

3. When sending a queen out to stud try and choose an older boy, ie ideally 4 years old or more who has scanned negatives himself and who has been proven to produce healthy HCM free kittens.

4. Keep your breeding cats for longer and keep kittens for breeding from older negative scanned parents where possible. Do not sell cats for breeding from young parents as they may develop HCM later. Obviously you have to be realistic about this but even if you avoid selling or keeping breeding kittens from studs under 2 this will help.

5. Consider use of Deslorelin (contraceptive implant- “Suprelorin (Virbac Ltd)” to prevent cats breeding for a couple of years while they mature to an age when echo screening more valid. This product is not licensed for cats but it is a recognised off label use and vets in practice are increasingly using it for long term contraception as it has none of the undesirable side effects of progestqagen contraceptives.

6. Even if you are unable to get all your breeding cats scanned every year always get a thorough auscultation of the chest done as close to mating as possible. Although it is true that not all cats affected with HCM develop a heart murmur , many do. A murmur suddenly audible in a young cat whose heart sounded normal previously may have HCM and should be investigated further by echocardiography before mating. It is a good idea to check the heart of all cats before each mating especially if some time has passed since the last HCM scan. This is especially important in young cats mated at around a year who will not yet have had their first booster. A loud systolic murmur developing in the first year is a common finding in young homozygous cats with a severe early onset form of HCM. It would be terrible to breed from such a cat for the sake of a few minutes spent listening to its chest. A pre-mating health check is quite a good idea for other reasons and an opportunity to check for any health problems or anatomical defects, perform an FIV/FeLV blood test if needed and even trim the cat’s nails for safety all at the same time.

7. Echocardiography – when and how often? The ideal is to scan all your cats annually. In females try and do this as close to mating as possible to reduce the risk of missing changes developing between the scan and mating. If holding a queen back it does not matter if the scan interval is longer than a year – just get it done shortly before the next mating. Conversely if your queen is fit to have another litter a month or two before the annual scan is due it is a good idea to get it done early to be on the safe side. If you can’t afford to scan all your cats at least do the males. The reasons for this is that males tend to develop changes earlier than females and they have the potential to produce more kittens. If cost is an issue a few things to note are:

• Vet schools tend to be a bit cheaper than private referral practices and it has been possible to negotiate a substantial discount for group sessions where several breeders all take their cats on the same day.

• You might be lucky enough to find a vet with an RCVS qualification at a local practice who is not on the list of scanners who are approved by the Veterinary Cardiovascular Society (VCS). Any vet with an RCVS qualification eg certificate or diploma in veterinary cardiology, is qualified to scan hearts although it is a good idea to ask questions about how much experience they have had in scanning cats. Some may not want to join the scanning list as they may be too busy to do routine scanning for breeders but might be perfectly competent and happy to do it for their own clients.

• The list of approved scanners (see below) is quite long now and published on the website of VCS.

8. An additional strategy is to advise breeders to maintain contact with the owners of any retired breeding cats, so that they become aware of any heart problems diagnosed in the future.

WHAT IS THE GCCF DOING ABOUT HCM?

The GCCF Genetics Committee is very concerned about HCM in many breeds and is currently considering ways of incorporating test requirements into registration and breeding policies. It is emphasized that most of the proposals below are still under discussion.

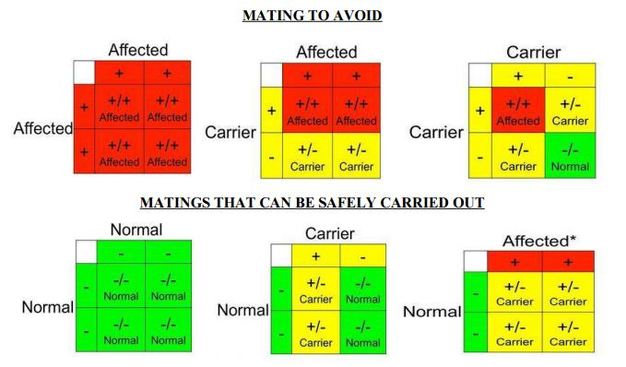

1. Where a validated DNA test exists eg Maine Coon and Ragdoll A valid DNA test certificate will be required for active registration. Only nomal cats(N/N) will be eligible for the full register. Heterozygous cats (N/H) will be allowed on the Genetic register providing evidence shows that (as with Ragdolls), the mortality in heterozygous cats is not significantly different from normal cats.

Advice in the breeding policy will be to only mate heterozygous cats with normal cats and to try and replace heterozygous cats with normal offspring as soon as possible. In this way it will be possible to eliminate the specific HCM gene over a relatively small number of generations without compromising the size of the gene pool. All untested cats and those which are homozygous (H/H) for the specific HCM gene will only be eligible for non-active registration. It will be a strong recommendation that all homozygous cats are neutered, preferably before leaving the breeder to ensure no accidental matings occur.

The Ragdoll BAC has recently become the first to incorporate a DNA testing scheme into its registration policy.

2. Where no validated DNA test exists eg Bengal, British Shorthair, NFC, Sphynx. This is a much more difficult situation. We feel a system of recording a cat’s echocardiography results is needed so breeders and kitten buyers know the status of cats they are using. The system would need to be separate from the existing registration policy as the cats echocardiography result is a changeable parameter.

Owners of active registered cats would be required to submit an HCM report form from an approved cardiologist. The cats status and date of test would be recorded with its registration details and there would be a facility for breeders to view and print the record to show to those who need it eg kitten buyers, owners of visiting queens or public studs. This data would remain on a cats file until replaced by a later test result. If an owner does not submit a test result the cats HCM status will be recorded as unknown. If an owner fails to submit a test within 13 months of the last one the cats current HCM status would revert to unknown although a note of the previous test result and date will remain on the record as historical data. Initially the system would be voluntary but after a trial period to see how acceptable it is to breeders, submission of an annual HCM scan report could become compulsory. The suggestion has been made that all cats scanning positive for HCM would be transferred to the non-active register free of charge when their result is submitted. The advice in the breeding policy will of course be that they are neutered.

A definite concern is that not enough breeders will enthusiastically support any screening scheme because of the cost, travel distance, frequency and lack of definitive outcome, whereas DNA testing is cheap by comparison and usually a one off. The only penalty that can be adopted by a registry is not to register the offspring from the non-tested for breeding in future, and that could deplete the gene pool and lead to other problems associated with lack of genetic diversity. Breeders have the possibility of using at least two, possibly three, other registries that are not likely to require such tests. They could also screen only occasionally and not bother registering the kittens at all at other times adding to the back yard breeder problem of unregistered kittens. There are obvious difficulties with such a scheme and hopefully a valid DNA test that detects the majority of affected cats will become available in Bengals soon.

3. Breeds with valid DNA test where other genetic mutations are known to be a cause of significant proportion of HCM cases. Eg Maine Coon and probably many other breeds in the future.

Obviously it is necessary for breeders to continue to scan their cats annually in situations where HCM occurs in cats that test negative on a breed specific DNA test.

In conclusion I think that, in the absence of a DNA test, the recording of HCM status to give greater transparency combined with a Code of Good Practice that breeders should do their best to follow could help to reduce the incidence and severity of HCM in our lovely breed. Langford Veterinary Diagnostics are currently collecting DNA samples (with owner’s permission) from every Bengal attending the Feline Centre for echoicardiography. I would strongly encourage everyone to contribute to the HCM research fund and also provide practical help by submitting DNA samples when requested by those doing the research. Once a test is developed it will also be much easier to collect data to provide sound evidence on which to base future regulatory strategy.

References (including on-line sources of further information):

Information about HCM from International Cat Care

http://icatcare.org/advice/cat-health/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy-hcm-and-testing

A concise review of HCM by Mark Kittelson and others.

http://hairlesshearts.org/index.php/what-is-hcm/feline-hcm-advice-for-breeders

Pawpeds Database Analysis – although this data has obvious limitations it does give insight into incidence of HCM in different breeds.

http://www.ig-hgk.de/html/pawpeds-database-analysis.html

Veterinary Cardiovascular Society List of Approved Cardiologists

http://www.bsavaportal.com/vcs/Information/HeartTesting/Dopplerechocardiographyexamination.aspx

This list is not exhaustive as only includes veterinary cardiologists who have chosen to join the Veterinary Cardiovascular Society. Any veterinary surgeon with an RCVS or European qualification in cardiology is qualified to perform echocardiography to screen for HCM and other heart diseases. It is worth asking your local practice to find out if any vets are suitably qualified before travelling miles to one on the VCS list. The recognized qualifications are:

RCVS: Cert VC, DVC, Cert SAC, Cert SAM (cardiology module)

European: Dip ECVIM-CA

Here is a link to the GCCF statement regarding HCM:

http://www.gccfcats.org/Portals/0/HCM%20Policy.pdf?ver=2017-03-30-094953-530

GENETICS

Early studies in a colony of Maine Coons indicated that HCM is caused by a defect in an autosomal dominant gene. However the situation is nowhere near as simple as that. In common with many other genetic diseases the defective gene shows extremely varied expression. Certainly there is incomplete dominance and in DNA tested Ragdolls and Maine Coons, cats with one copy of the gene (heterozygous) seem to be less severely affected than cats with two copies of the defective gene (homozygous).

DNA tests for the defective HCM gene are now commercially available in Maine Coons and Ragdolls. Studies in these breeds confirm this is the case. An interesting study in DNA tested Ragdolls showed very little difference in mortality to 12 years between normal and heterozygous cats. In homozygous cats there was around 50% mortality by 5 years but 20% of cats were still alive at 12 years showing that HCM is not necessarily a death sentence. It is likely that a similar situation exists in Bengals. It certainly explains why kittens who die of HCM at an early age can be born to parents (presumably heterozygous) who show no sign of HCM by echocardiography as young adults. In terms of the clinical picture the pattern can resemble a disease caused by a recessive gene. It also means that echocardiography alone does not necessarily detect affected cats – especially heterozygous ones. For this reason it is not yet possible to completely prevent HCM by echocardiography alone.

Another problem is that there are also many different mutations of this gene so it is possible that a DNA test that is developed to identify a single mutation may not detect all cases of HCM in a breed if the problem is due to several different mutations. This does seem to be the case in Maine Coons where cases of HCM have been recorded in cats which give a Normal result with the DNA test. In this situation breeders may need to continue to scan their cats annually.

PREVENTION OF HCM IN BENGALS

Sadly we have no validated DNA test for HCM in Bengals yet. Research is ongoing and recent advances have been made so hopefully a commercial test will be available but probably not for 2-3 more years. We must also remember that any mutation for which a test is developed may not be the only one.

The only way we have of detecting sub-clinical HCM in our cats is screening by echocardiography The main problem with this is that variable expression of the HCM gene means that many affected cats do not develop detectable echocardiographic changes until they are more than 1-2 years, ie the ages when most of us want to start breeding from our cats. Some cats, especially heterozygous ones, may never develop clinical signs of HCM and unless scanned well into middle age long after they have been neutered and retired we will never know they were affected. Other problems are cost as the scan needs to be repeated annually and there may be a considerable distance to travel to a qualified cardiologist.

IN THE MEANTIME, WHAT CAN WE DO TO REDUCE THE RISK?

1.Buy from echo tested lines. Now that more people scanning their cats annually under university schemes or other qualified veterinary cardiologists it is easier to buy a kitten from echo screened parents and where possible the grandparents also.

2. Do research pedigrees when buying breeding cats. Some on-line resources giving HCM test results for Bengals are available but these are incomplete and may not always be valid.

3. When sending a queen out to stud try and choose an older boy, ie ideally 4 years old or more who has scanned negatives himself and who has been proven to produce healthy HCM free kittens.

4. Keep your breeding cats for longer and keep kittens for breeding from older negative scanned parents where possible. Do not sell cats for breeding from young parents as they may develop HCM later. Obviously you have to be realistic about this but even if you avoid selling or keeping breeding kittens from studs under 2 this will help.

5. Consider use of Deslorelin (contraceptive implant- “Suprelorin (Virbac Ltd)” to prevent cats breeding for a couple of years while they mature to an age when echo screening more valid. This product is not licensed for cats but it is a recognised off label use and vets in practice are increasingly using it for long term contraception as it has none of the undesirable side effects of progestqagen contraceptives.

6. Even if you are unable to get all your breeding cats scanned every year always get a thorough auscultation of the chest done as close to mating as possible. Although it is true that not all cats affected with HCM develop a heart murmur , many do. A murmur suddenly audible in a young cat whose heart sounded normal previously may have HCM and should be investigated further by echocardiography before mating. It is a good idea to check the heart of all cats before each mating especially if some time has passed since the last HCM scan. This is especially important in young cats mated at around a year who will not yet have had their first booster. A loud systolic murmur developing in the first year is a common finding in young homozygous cats with a severe early onset form of HCM. It would be terrible to breed from such a cat for the sake of a few minutes spent listening to its chest. A pre-mating health check is quite a good idea for other reasons and an opportunity to check for any health problems or anatomical defects, perform an FIV/FeLV blood test if needed and even trim the cat’s nails for safety all at the same time.

7. Echocardiography – when and how often? The ideal is to scan all your cats annually. In females try and do this as close to mating as possible to reduce the risk of missing changes developing between the scan and mating. If holding a queen back it does not matter if the scan interval is longer than a year – just get it done shortly before the next mating. Conversely if your queen is fit to have another litter a month or two before the annual scan is due it is a good idea to get it done early to be on the safe side. If you can’t afford to scan all your cats at least do the males. The reasons for this is that males tend to develop changes earlier than females and they have the potential to produce more kittens. If cost is an issue a few things to note are:

• Vet schools tend to be a bit cheaper than private referral practices and it has been possible to negotiate a substantial discount for group sessions where several breeders all take their cats on the same day.

• You might be lucky enough to find a vet with an RCVS qualification at a local practice who is not on the list of scanners who are approved by the Veterinary Cardiovascular Society (VCS). Any vet with an RCVS qualification eg certificate or diploma in veterinary cardiology, is qualified to scan hearts although it is a good idea to ask questions about how much experience they have had in scanning cats. Some may not want to join the scanning list as they may be too busy to do routine scanning for breeders but might be perfectly competent and happy to do it for their own clients.

• The list of approved scanners (see below) is quite long now and published on the website of VCS.

8. An additional strategy is to advise breeders to maintain contact with the owners of any retired breeding cats, so that they become aware of any heart problems diagnosed in the future.

WHAT IS THE GCCF DOING ABOUT HCM?

The GCCF Genetics Committee is very concerned about HCM in many breeds and is currently considering ways of incorporating test requirements into registration and breeding policies. It is emphasized that most of the proposals below are still under discussion.

1. Where a validated DNA test exists eg Maine Coon and Ragdoll A valid DNA test certificate will be required for active registration. Only nomal cats(N/N) will be eligible for the full register. Heterozygous cats (N/H) will be allowed on the Genetic register providing evidence shows that (as with Ragdolls), the mortality in heterozygous cats is not significantly different from normal cats.

Advice in the breeding policy will be to only mate heterozygous cats with normal cats and to try and replace heterozygous cats with normal offspring as soon as possible. In this way it will be possible to eliminate the specific HCM gene over a relatively small number of generations without compromising the size of the gene pool. All untested cats and those which are homozygous (H/H) for the specific HCM gene will only be eligible for non-active registration. It will be a strong recommendation that all homozygous cats are neutered, preferably before leaving the breeder to ensure no accidental matings occur.

The Ragdoll BAC has recently become the first to incorporate a DNA testing scheme into its registration policy.

2. Where no validated DNA test exists eg Bengal, British Shorthair, NFC, Sphynx. This is a much more difficult situation. We feel a system of recording a cat’s echocardiography results is needed so breeders and kitten buyers know the status of cats they are using. The system would need to be separate from the existing registration policy as the cats echocardiography result is a changeable parameter.

Owners of active registered cats would be required to submit an HCM report form from an approved cardiologist. The cats status and date of test would be recorded with its registration details and there would be a facility for breeders to view and print the record to show to those who need it eg kitten buyers, owners of visiting queens or public studs. This data would remain on a cats file until replaced by a later test result. If an owner does not submit a test result the cats HCM status will be recorded as unknown. If an owner fails to submit a test within 13 months of the last one the cats current HCM status would revert to unknown although a note of the previous test result and date will remain on the record as historical data. Initially the system would be voluntary but after a trial period to see how acceptable it is to breeders, submission of an annual HCM scan report could become compulsory. The suggestion has been made that all cats scanning positive for HCM would be transferred to the non-active register free of charge when their result is submitted. The advice in the breeding policy will of course be that they are neutered.

A definite concern is that not enough breeders will enthusiastically support any screening scheme because of the cost, travel distance, frequency and lack of definitive outcome, whereas DNA testing is cheap by comparison and usually a one off. The only penalty that can be adopted by a registry is not to register the offspring from the non-tested for breeding in future, and that could deplete the gene pool and lead to other problems associated with lack of genetic diversity. Breeders have the possibility of using at least two, possibly three, other registries that are not likely to require such tests. They could also screen only occasionally and not bother registering the kittens at all at other times adding to the back yard breeder problem of unregistered kittens. There are obvious difficulties with such a scheme and hopefully a valid DNA test that detects the majority of affected cats will become available in Bengals soon.

3. Breeds with valid DNA test where other genetic mutations are known to be a cause of significant proportion of HCM cases. Eg Maine Coon and probably many other breeds in the future.

Obviously it is necessary for breeders to continue to scan their cats annually in situations where HCM occurs in cats that test negative on a breed specific DNA test.

In conclusion I think that, in the absence of a DNA test, the recording of HCM status to give greater transparency combined with a Code of Good Practice that breeders should do their best to follow could help to reduce the incidence and severity of HCM in our lovely breed. Langford Veterinary Diagnostics are currently collecting DNA samples (with owner’s permission) from every Bengal attending the Feline Centre for echoicardiography. I would strongly encourage everyone to contribute to the HCM research fund and also provide practical help by submitting DNA samples when requested by those doing the research. Once a test is developed it will also be much easier to collect data to provide sound evidence on which to base future regulatory strategy.

References (including on-line sources of further information):

Information about HCM from International Cat Care

http://icatcare.org/advice/cat-health/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy-hcm-and-testing

A concise review of HCM by Mark Kittelson and others.

http://hairlesshearts.org/index.php/what-is-hcm/feline-hcm-advice-for-breeders

Pawpeds Database Analysis – although this data has obvious limitations it does give insight into incidence of HCM in different breeds.

http://www.ig-hgk.de/html/pawpeds-database-analysis.html

Veterinary Cardiovascular Society List of Approved Cardiologists

http://www.bsavaportal.com/vcs/Information/HeartTesting/Dopplerechocardiographyexamination.aspx

This list is not exhaustive as only includes veterinary cardiologists who have chosen to join the Veterinary Cardiovascular Society. Any veterinary surgeon with an RCVS or European qualification in cardiology is qualified to perform echocardiography to screen for HCM and other heart diseases. It is worth asking your local practice to find out if any vets are suitably qualified before travelling miles to one on the VCS list. The recognized qualifications are:

RCVS: Cert VC, DVC, Cert SAC, Cert SAM (cardiology module)

European: Dip ECVIM-CA

Here is a link to the GCCF statement regarding HCM:

http://www.gccfcats.org/Portals/0/HCM%20Policy.pdf?ver=2017-03-30-094953-530

PROGRESSIVE RETINAL ATROPHY IN THE BENGAL CAT

An article written by Sue Moreland MRCVS, Bengal CC Committee member and GCCF Veterinary Officer

An article written by Sue Moreland MRCVS, Bengal CC Committee member and GCCF Veterinary Officer

Cases of blindness in young Bengals have been reported in the USA for a number of years, and I have also heard anecdotal reports of a few cases in the UK. The condition has now been fully studied by Leslie Lyons and her team at UC Davis, California, and a paper was published in August 2015 after six years of work.

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is the name given to a condition where there is spontaneous degeneration of the light receptor cells (rods and cones) in the retina. This is progressive, hence the name, causing the animal to eventually go blind. Hereditary PRA affects many animals including man. A number of different genes have been identified in dogs and cats These are specific to the breed concerned and the condition varies in age and time of onset depending on the genetic type. In cats, hereditary PRA is recognised in a number of breeds including Abyssinian, Persian, Norwegian Forest and Siamese and DNA tests are already available for three forms of the disease.

The recent study at Davis has confirmed that Bengals also suffer from a hereditary form of PRA. It has a very early onset and changes can be detected in the retina by ophthalmoscopy as young as 8 weeks. The speed of progression is quite variable and but cats show clinical signs of blindness by one year. However cats are very good at coping with loss of vision and owners may not become aware that their cat is blind until they are considerably older.

The study has also shown that the disease is due to a defect in an autosomal recessive gene that is different from the mutation causing PRA in other breeds. Heterozygous cats who carry only one copy of the defective gene do not develop the disease. Homozygous cats who possess two copies of the defective gene are always affected and sadly will go blind.

Fortunately Leslie and her team have identified the gene responsible and a DNA test has been developed, which will enable breeders to identify carrier and affected cats at an early age by submitting a cheek swab or blood sample. Less fortunately the test hit problems shortly after it was introduced earlier this year. It was giving a false positive result and a number of mature adult cats with normal sight tested positive.

The test had to be suspended until the reason for the error was detected. The reason is quite interesting. It was found that the rogue PRA gene was confined to domestic cat DNA. The comparable normal gene on an ALC derived region of the chromosome was slightly different to the normal domestic cat gene. The test system detected the difference from normal domestic DNA in the ALC derived gene and flagged it up as a positive. Now that the problem has been identified the lab at UC Davis has announced that the test will be commercially available again in a few month’s time.

Although it is hoped that the frequency of the PRA gene in UK Bengals is low I think it is important we use the test when it becomes available. The GCCF are likely to make it a requirement for all imports on to the Active Register. If results indicate a significant frequency in UK Bengals we must consider introducing a testing requirement and genetic register into the registration policy. If we do this it will be a relatively simple matter to rid the gene pool of this serious condition without seriously depleting it. Although homozygous cats would need to be removed from the breeding programme it will be perfectly safe to breed with heterozygous cats provided they are mated with normal cats.

More information about the current status of the DNA test can be found on the UC Davis VGL website below.

https://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/cat/BengalPRA.php

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is the name given to a condition where there is spontaneous degeneration of the light receptor cells (rods and cones) in the retina. This is progressive, hence the name, causing the animal to eventually go blind. Hereditary PRA affects many animals including man. A number of different genes have been identified in dogs and cats These are specific to the breed concerned and the condition varies in age and time of onset depending on the genetic type. In cats, hereditary PRA is recognised in a number of breeds including Abyssinian, Persian, Norwegian Forest and Siamese and DNA tests are already available for three forms of the disease.

The recent study at Davis has confirmed that Bengals also suffer from a hereditary form of PRA. It has a very early onset and changes can be detected in the retina by ophthalmoscopy as young as 8 weeks. The speed of progression is quite variable and but cats show clinical signs of blindness by one year. However cats are very good at coping with loss of vision and owners may not become aware that their cat is blind until they are considerably older.

The study has also shown that the disease is due to a defect in an autosomal recessive gene that is different from the mutation causing PRA in other breeds. Heterozygous cats who carry only one copy of the defective gene do not develop the disease. Homozygous cats who possess two copies of the defective gene are always affected and sadly will go blind.

Fortunately Leslie and her team have identified the gene responsible and a DNA test has been developed, which will enable breeders to identify carrier and affected cats at an early age by submitting a cheek swab or blood sample. Less fortunately the test hit problems shortly after it was introduced earlier this year. It was giving a false positive result and a number of mature adult cats with normal sight tested positive.

The test had to be suspended until the reason for the error was detected. The reason is quite interesting. It was found that the rogue PRA gene was confined to domestic cat DNA. The comparable normal gene on an ALC derived region of the chromosome was slightly different to the normal domestic cat gene. The test system detected the difference from normal domestic DNA in the ALC derived gene and flagged it up as a positive. Now that the problem has been identified the lab at UC Davis has announced that the test will be commercially available again in a few month’s time.

Although it is hoped that the frequency of the PRA gene in UK Bengals is low I think it is important we use the test when it becomes available. The GCCF are likely to make it a requirement for all imports on to the Active Register. If results indicate a significant frequency in UK Bengals we must consider introducing a testing requirement and genetic register into the registration policy. If we do this it will be a relatively simple matter to rid the gene pool of this serious condition without seriously depleting it. Although homozygous cats would need to be removed from the breeding programme it will be perfectly safe to breed with heterozygous cats provided they are mated with normal cats.

More information about the current status of the DNA test can be found on the UC Davis VGL website below.

https://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/cat/BengalPRA.php

CLUB MEMBER GINA STOKES TALKS ABOUT HER PERSONAL EXPERIENCE WITH PRA

“We had our first Bengal who we called Spice when I started working part time, I had always loved the breed but it had never been the right time. We decided to buy a queen on the active so we had the option to breed if we wanted to, my mum used to breed Burmese and always enjoyed it. To cut a long story short we fell in love with the breed and decided we wanted to breed from her.

She had had a PKDEF test and was genetically clear and I intended to HCM test her. I read about the new PRA-b test offered by UC Davis on the Bengal Cat Club Facebook page which I had just joined at the time. The test was new (Jan 2016) and there didn't seem to be many that had tested. I must admit as soon as I saw it my heart sank, 6 months earlier I had asked the vet to check her vision as she was bumping into things, but the vet had checked her thoroughly and said there was not a problem, this could explain it. At the time we put it down to our inexperience with the breed and perhaps they were just quite clumsy! I had to test straight away as I didn't want to risk producing blind kittens.

I want to try my upmost to help improve the breed and produce healthy kittens otherwise I can't see the point in breeding. I am a bit of a perfectionist, so I must admit I struggle to accept anything less! The swabs were really easy to do, just a couple of cotton buds (cue tips), roll them round in their mouths to collect cells from their cheek and send them off to America. It took almost 2 weeks to arrive (have since sent other swabs and have only taken 5 days) and I waited nervously when I received an email informing me the swabs had been received. Two days later and the results were in - PRA/PRA, therefore affected. I asked them to run again because the vet had said everything was okay, they did and it still came back affected. I was heartbroken and couldn't believe the vet got it so wrong.

As she turned 2 years old I noticed her degrading vision had turned into complete blindness. I feel so sad for her, such a young active cat, I look into her eyes, hold her for a cuddle and just look into nothingness. Selfish of me as she copes well and is happy but I feel a sense of loss for the cat she should be, I should be able to look at her and she look back at me with her big green eyes but she just sees straight through me (or doesn't as the case maybe).

Still, breeders are not testing, and it is so cheap and quick and easy to do there really is no excuse. Please, we need to try and breed this out of Bengals, I may be new to the breed but I do believe that if you don't health test you are really playing with fire, DNA testing is so easy.”

Gina Stokes

She had had a PKDEF test and was genetically clear and I intended to HCM test her. I read about the new PRA-b test offered by UC Davis on the Bengal Cat Club Facebook page which I had just joined at the time. The test was new (Jan 2016) and there didn't seem to be many that had tested. I must admit as soon as I saw it my heart sank, 6 months earlier I had asked the vet to check her vision as she was bumping into things, but the vet had checked her thoroughly and said there was not a problem, this could explain it. At the time we put it down to our inexperience with the breed and perhaps they were just quite clumsy! I had to test straight away as I didn't want to risk producing blind kittens.

I want to try my upmost to help improve the breed and produce healthy kittens otherwise I can't see the point in breeding. I am a bit of a perfectionist, so I must admit I struggle to accept anything less! The swabs were really easy to do, just a couple of cotton buds (cue tips), roll them round in their mouths to collect cells from their cheek and send them off to America. It took almost 2 weeks to arrive (have since sent other swabs and have only taken 5 days) and I waited nervously when I received an email informing me the swabs had been received. Two days later and the results were in - PRA/PRA, therefore affected. I asked them to run again because the vet had said everything was okay, they did and it still came back affected. I was heartbroken and couldn't believe the vet got it so wrong.

As she turned 2 years old I noticed her degrading vision had turned into complete blindness. I feel so sad for her, such a young active cat, I look into her eyes, hold her for a cuddle and just look into nothingness. Selfish of me as she copes well and is happy but I feel a sense of loss for the cat she should be, I should be able to look at her and she look back at me with her big green eyes but she just sees straight through me (or doesn't as the case maybe).

Still, breeders are not testing, and it is so cheap and quick and easy to do there really is no excuse. Please, we need to try and breed this out of Bengals, I may be new to the breed but I do believe that if you don't health test you are really playing with fire, DNA testing is so easy.”

Gina Stokes

PYRUVATE KINASE DEFICIENCY (PK-Def)

An article written by Claire Workman

An article written by Claire Workman

Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency (PK-Def), is a genetic condition known in the Bengal breed (as well as some other breeds), which causes anaemia in affected cats, including sometimes a severe form of anaemia which can be life threatening.

The good news is that it is easy to detect. A simple swab taken from the inner cheek is sent to a laboratory for testing to confirm the PK deficiency status of all individual breeding cats. This test is a one off from Langford Vets costing around £33 for one cat and £45 for two cats and further reductions for more cats. Once the status of individual breeding cats is known this condition can be easily eradicated through selective breeding.

Cats are confirmed as Normal, Carrier or Positive. So far in the UK only a small percentage of Bengals have tested positive (around 2%), however, around 27% are carriers of the gene. It is therefore important for breeders to know the status of ALL their cats to avoid producing any positive kittens. This is easily avoided by ensuring only Normal x Normal or Normal x Carrier matings are performed. Test swabs can be obtained and sent back to Langford Vets at Bristol University: http://www.langfordvets.co.uk/diagnostic-laboratories There is a reduced rate for our Bengal Cat Club members. Please contact us for the code. Please see the diagrams below as to how PK-Def is inherited.

The good news is that it is easy to detect. A simple swab taken from the inner cheek is sent to a laboratory for testing to confirm the PK deficiency status of all individual breeding cats. This test is a one off from Langford Vets costing around £33 for one cat and £45 for two cats and further reductions for more cats. Once the status of individual breeding cats is known this condition can be easily eradicated through selective breeding.

Cats are confirmed as Normal, Carrier or Positive. So far in the UK only a small percentage of Bengals have tested positive (around 2%), however, around 27% are carriers of the gene. It is therefore important for breeders to know the status of ALL their cats to avoid producing any positive kittens. This is easily avoided by ensuring only Normal x Normal or Normal x Carrier matings are performed. Test swabs can be obtained and sent back to Langford Vets at Bristol University: http://www.langfordvets.co.uk/diagnostic-laboratories There is a reduced rate for our Bengal Cat Club members. Please contact us for the code. Please see the diagrams below as to how PK-Def is inherited.

lyThe International Cat Care provides a good information source for further reading on PKDef. Click the link below to go to their page:

http://www.icatcare.org/advice/cat-health/pyruvate-kinase-pk-deficiency

Also, a good source of information about many aspects of Bengal health can be found here: http://www.bengalbreedersukunited.co.uk/

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

feline_blood_groups.docx

what_blood_types_do_cats_have.docx

early_neutering.docx

new_breeders.docx

http://www.icatcare.org/advice/cat-health/pyruvate-kinase-pk-deficiency

Also, a good source of information about many aspects of Bengal health can be found here: http://www.bengalbreedersukunited.co.uk/

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

feline_blood_groups.docx

what_blood_types_do_cats_have.docx

early_neutering.docx

new_breeders.docx